The Legend.

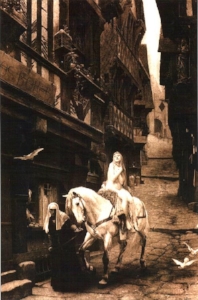

John Collier's painting of the ride.

The story most people knew is the one Tennyson tells in his poem of 1842.

The poor of Coventry complain to Lady Godiva that they are starving. Moved by pity, she asks her grim and heartless husband, Earl Leofric, to lift the taxes. He refuses. She nags him. Exasperated he says “I’ll lift the taxes if you ride naked round the city”.

Before she does this, she does a deal with the townsfolk. They will stay off the street and keep the windows shut while she rides round, clad in nothing but her hair.

One dastardly individual, a tailor called Tom, who Tennyson doesn’t have to name, tries to bore a peep hole so he can watch her riding past but his eyes are blasted, in Tennyson’s version by “the powers”, and fall out before he gets to see her.

She rides round the city, returns, and Leofric lifts the taxes.

The Legend begins

The VCH states that the earliest surviving version of the story of the ride occurs in the Chronicle of Roger of Wendover (who died in 1237).

THE LEGEND OF LADY GODIVA

However, the countess Godiva, a devotee of the mother of God, desiring to free the town of Coventry from the heavy servitude of toll, often besought the earl, her husband, with earnest prayers to free the town from the said servitude and other troublesome exactions, by the guidance of Jesus Christ and his mother. The earl upbraided her for vainly seeking something so injurious to him and repeatedly forbade her to approach him again on the subject. Nevertheless, in her feminine pertinacity she exasperated her husband with her unceasing request and extorted from him the following reply: 'Mount your horse naked', he said, 'and ride through the market place of the town, from one side right to the other, while the people are congregated, and when you return you shall claim what you desire'. And the countess answered, 'And if I will do this, will you give me your permission?' And he said, 'I will.' Then the countess, beloved of God, accompanied by two soldiers, as it is said, mounting her horse naked, loosed her hair from its bands, so veiling the whole of her body, and thus passing through the market place she was seen by nobody (a nemine visa) except for her very white legs. Her journey completed, she returned rejoicing to her husband, and, as he wondered at the deed, she demanded of him what she had asked. Then Earl Leofric freed the town of Coventry and its inhabitants from the said servitude, confirming what he had done with a charter.

It’s written in Latin, by a Monk, and the time lapse is important. Because it’s written in Latin, I have to rely on someone else’s translation. So this is taken from the VCH Warwickshire which I compared with Donoghue, who quotes other early versions.

If you compare these with Tennyson’s 1842 poem, then there are some significant differences. There is no Peeping Tom and far from doing a deal with the Townspeople to stay indoors, Leofric stipulates that she has to ride 'through the market place of the town, from one side right to the other while the people are congregated and when you return you shall gain what you desire.'

Accompanied by two 'soldiers' 'the Countess mounted her horse naked, loosed her hair from its bands, so veiled the whole of her body except for her brilliantly white legs, passed through the market place unseen by anybody.'

The key to the whole story, I think, is not the fact that her name has been Latinized, or she’s been given a title, or the impracticalities of covering yourself with hair while riding a horse (on a day when obviously there was no wind).

It’s the assumptions that Wendover and Tennyson share that are revealing. In six hundred years, what doesn’t change in the story is the power imbalance between Godiva and Leofric.

She has no power, except her ability to nag him, while he has the right to impose or to remit taxes and tolls on the people of Coventry.

OF all the things that Leofric could ask her to do, why does he choose this one? None of the versions of the story adequately explain this choice.

Two things at least, are odd about Tennyson’s Lady G. The first is that her husband implicitly accuses her of hypocrisy, when he plays with the diamond at her ear, the implication is 'this would stop them from starving; your wealth is based on their starvation.' The second thing is that realistically she risks very little. The townsfolk, whether for love of her or simple self interest have a huge incentive to stay in doors and the 'Powers' (not God incidentally) look after her to the point of blinding some poor churl before he even gets to peek. So what does she risk? How is she heroic?

The history

Godiva is the Latin attempt at Godgifu. That simple act of renaming, which ignores cultural and linguistic conventions, (women’s names don’t end in A in the Nominative in Old English) is the real clue to the process by which an historical character came to be associated with something that probably never happened.

Godgiefu, or Godgifu, God’s gift, did exist and she did play an important role in the development of Coventry and late Anglo-Saxon England. She was the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia.

She wasn’t called 'Lady' because Earl was an office, not a title as such, and so there was no name for the Earl’s wife. In Anglo-Saxon documents she is 'The Earl’s wife' (just as today we talk about the 'prime minister’s husband'). Or his “gebedda”, his bed companion. (There’s nothing derogatory in the term, and can be used of either gender.)

Not much is known about her except her connection to Coventry and the fact that by 1067 she was one of the wealthiest women in England.

She and her husband founded, or re-established, a religious institution where Coventry now is, in about 1043, dedicating it to St Mary, St Osberg and All Saints.

There had already been a convent there that had been sacked by the Danes in or about 1016. Its Abbess, Osberg, had been martyred. Little is known about the early foundation or its abbess, except that she died and courtesy of Godiva and Leofric her head ended up on the altar in a jewel-spangled box.

The couple were noted benefactors, and amongst the things that they were supposed to have donated to their new establishment was a reliquary holding the arm of Saint Augustine of Hippo.

Stumbling over such little gems of information is what makes doing research for a project like Lady Godiva and Me so enthralling. But while it sent me spinning off on a productive sidetrack for now the digressions can wait.

Although her dates are sketchy, she outlived Leofric.

Before he died there is some evidence that Coventry may have become their chief residence, if not their permanent home.

Their granddaughter was twice a Queen. First of Wales, then married to the last Anglo-Saxon King of England, probably in a move designed to appease her brothers, whose activities in 1066 probably didn’t make Grandma proud. She was alive after the conquest, recorded as one of the richest women in England, and was buried by Leofric’s side in Coventry.

And the ride?

Remember that mistranslation.

How different the World

No photographs. No recorded voices. No twenty four hour news feed. No global geography worth the name. How limited knowledge and how awkward its diffusion. How poor its chances of survival.

The fact we even know there was a woman called Godgifu seems miraculous.

Unless you were a member of the court, you wouldn’t even know what the king looked like. The possibility of hearing his voice would be minimal. The families settled around Coventry would know the Earl and his wife, but that would be familiarity. How important context would be. How crucial the personalized links that verify your identity. Why your social role was such a definition.

And then think of how strange the world. Imagine distance measured by effort and time with no real global context and no predictability. Today if you Dropped an educated person down in the world somewhere and told them where they are, they’d have a sense of what lies in each direction. But for someone in Coventry in the 11th Century? If you went that way you reached Winchester, or London, and if you kept going, the coast, and France and then the pilgrim routes. That way, north, York, the sea lanes to Denmark. Vague cosmologies; detailed where the route is personally known, vague where it’s only hearsay. And the world beyond the known route, fading into vagueness. Peopled by strange possibilities.

Almost everything passed by word of mouth and stored in human memory. So the man who tells you about the things he saw when he was traveling, passed on in a game of Chinese whispers, with no way of checking the truth or the source.

The traveller who comes to your monastery and says…have you heard about the Earl’s wife. Have you heard what she did over in Coventry?

Reinventing the past

A 19th century dream of Coventry as it never way. Even the fact she's riding a version of side saddle is anachronistic.

The Latin legends, like the picture, ‘prove’ the fact that we reinvent the past by viewing it through the lens of our own assumptions. The 19th century pictures of Lady G (and she was a popular topic) show her in a Coventry that never existed and certainly doesn't look anything like the settlement that would have been there in the 11th century.

For the ride to have occurred we need a town, a developed community, a market place and a charter of Liberties. While Leofric and Godiva probably did have a residence in the 1050s, the "town" was an agricultural community growing up around the religious foundation. Think West Stow with a church.

Anglo-Saxon houses at the experimental site at West Stow

While riding round something that looked like West Stow is easier to imagine, the real reason why I'd bet a stack of currently devalued Australian Dollars she didn't do it, is that a free noble-woman in Anglo Saxon England possibly enjoyed legal and economic status that wouldn't be regained until the late 19th, early 20th century.

The flaw in the whole story is that any taxes or tolls levelled on the people of Coventry, that weren't the King's, and which couldn't be tampered with as the events of 1041 showed, went to Godgifu herself. She 'owned' the settlement at Coventry, not Leofric.

Unlike married women for the next eight hundred years, an Anglo-saxon wife could hold land in her own right. While not as rich as her husband, Godgifu was the wealthiest woman in England at the time of the Conquest.

Writing over a hundred years later, the first tellers of the tale simply couldn't imagine a world where married women held land independently of their husbands. Presumably neither could Tennyson, eight hundred years or so later...

Peeping Tom

The clock in Broadgate, Coventry, where Tom has his eyes blasted every hour.

One of the attractions of writing poetry about a historical subject is that you’re writing poetry not history. You can wander through areas where a lack of qualifications is no problem, and make links which no rational historian might accept. I extended that privilege into the world of the paraphilias: Voyeurism and exhibitionism.

Peeping Tom is a later addition to the story. He first appears in the 16th century, although the voyeuristic element has been introduced in earlier versions where it was Leofric who was perversely enjoying the sight of his wife.

The savagery of Tom's punishment feels as though we have slipped sideways into Grimm’s grimmest. Several commentators have pointed out at that he acts as a scapegoat to displace the charge of voyeurism. The man looking at the painting, the reader imagining the story, is not Peeping Tom, is not guilty. The picture is of a nude, not a naked woman, the viewer looks with the educated gaze of the connoisseur. The story of the ride is a tale of courage and compassion, not a work of pornography.

What the commentaries don’t do is reflect on how the arrival of Tom changes the story and shapes the image of Godiva.

The most powerful woman in your world is going to ride past. Naked. Do you look, or turn away.

1980s, Mrs. Thatcher? Wouldn’t look. No way, no how.

2008, Anna Bligh, Qld Premier is about to ride down the road. Nope.

Tom’s act shifts the story so that Godiva is suddenly worth looking at. So much so that he jeopardizes the deal. Godgifu, was short or tall, thin or fat. For all we know she had a face like the front of a shield wall. Enter Tom, and suddenly Godgifu becomes Godiva, becomes an object of desire. Just as people create ideal versions of people they don't know well. No longer an individual; an inhuman ideal.

For the ones like us/who are oppressed by the figures of Beauty.

Reading about 18th century attitudes to the sublime (as you do) I came across this quote:

The need to destroy the power of the beautiful other is an outcome of her very purity, her separateness from the perceiver’s interest. Thus as Mary Shelley presents it, the purity of Kantian beauty is a deprivation that inevitability evokes the enmity of the perceiver, who wants to punish it for its inaccessibility and distance. When woman is the embodiment of that beauty, she is at risk. (Wendy Steiner. The Trouble With Beauty. P17)

The header quote is from a Cohen song. It could just as easily be:

'Beauty is the first touch of terror/and it awes us so much/because it so coolly disdains to destroy us' which thanks to google I’ve learned is a misremembered quotation from Rilke.

Leofric and Tom can be read as representing two responses to The Other. In this case the Other is a beautiful woman. (Lady G doesn't have to be beautiful, but it works just as well if we play along with that idea).

Leofric, in my version, loves his wife. She is God's gift to him. She makes him want to be better, to honour her or words to some such thought. It's like the two players in a duet where one is perceived as being so much better than the other. The positive and healthy response is to rise to the challenge, to want to play better, and in fact to play better. Leofric loves her because she takes his performance as a human being to somewhere he can't get on his own and because he has the self-confirming sense that the feeling is mutual, that he does the same thing for his wife. You could say he's the ideal adult male in an ideal relationship. A bit radical really, a happily married man who loves his wife and is loved by her. Not many of them in fiction.

Tom on the other hand (who seems to me to be very adolescent) experiences nothing but a revelation of beauty. He doesn't see a flesh and blood woman. He sees beauty with a capital B riding past and when he turns back to his little room that is both literal and symbol of his life, he realises he cannot imagine her there, cannot believe she would even give him the time of day if they passed in the street.

Instead of feeling enriched by his encounter with this Other he feels inadequate. He can imagine that body in his bed, but not at his table, or by his fire...and because of that he feels small and ugly and diminished...so he will quickly start to hate her even though she doesn't know that he exists...and his sexual fantasies about her will sour and become an act of psychic revenge. He is blinded to his own true nature. (Trapped in his little room, he doesn't see that he could just as easily step out of it) and to hers because he doesn't see her clearly enough.. Godgifu, for him, becomes Godiva. Like everyone else, he invents versions of other people, only in his case his version is an impossible ideal that diminishes him.

His ability to see clearly is destroyed.

St Augustine

Both Leofric and Godgifu were remembered as being pious and generous benefactors to religious institutions.

One of many great moments of researching Lady G was the discovery that she and her husband donated a reliquary containing the arm of Augustine of Hippo to their new foundation at Coventry. Good research opens up doors you didn’t know were there.

The idea that part of the writer of the Confessions etc ended up IN Coventry of all places is almost comic. The fact that Leofric may have been given it as his reward for his help in Edward’s raid on his mother’s treasury, given the status given to mothers and Grandmothers in Lady G, is my irony, not history’s.

Augustine is one of the great deniers. According to him four things vexed the mind and should be avoided: Desire, Joy, Fear and Sorrow. There were three sins: The lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the ambitions of the world. Doesn’t leave a lot untainted. And you can see why people used to say that Catholics didn’t believe in life after birth.

The writings of a man who may not have been quite right in the head by modern standards had such an effect that over a thousand years later it was still shaping the way I was expected to behave from primary school onwards. That intrigues me.

Why is history the record of the followers of the great deniers and their attempts to impose their moral bleakness on the rest of us? Juxtapose a naked body and the long reach of a dead man’s withered arm. Why is the withered arm the default choice for so many?