For Lady G.

When they say that you should stay indoors;

ride on.

When they claim this world cannot be yours;

ride on.

Though they build their words around you,

definitions to confound you,

step out and trust yourself,

then ride on.

The person they’re describing can’t be you.

You’re always so much more than what you do.

In your thinking and your actions

there is beauty, not in factions.

Trust the judgment you’ve developed,

and ride on

Frightened strangers in their shuttered rooms;

ride on,

past the priests predicting that you’re doomed;

ride on.

Reject all binary oppositions,

as unthinking superstitions,

step out, and trust yourself,

and then ride on.

The book is split into four sections. In the first three the swirling voices of the city's present and past are not identified in anyway, but occur, with one exception, in blocks of twelve lines..

From The Prologue

These words worked the long day Harold died,

when Norman French swept up the slope of Senlac Hill

and English grammar broke and bled into the dusk.

Harold’s rotted in his unmarked grave,

but the tattered remnants of his word hoard

still colonize the globe. Linguistic vertigo:

peer into the word, encounter gravity of meaning,

until there’s nothing there but drop. You fall

and find yourself, again, there in the shield wall

beating battle-axe on war board, chanting

‘Out! Out! Out!’ as the chain-mailed tide,

grey as the Channel, flows up the hill.

From part one; Anglo-Saxon to Medieval, History to Ledgend

These are not Angles, these are Angels.

So Gregory, the patron saint of puns,

dispatched that other Augustine,

intolerant, misogynist, ambassador of love.

‘Life,’ said the pagan, ‘is like the tiny bird

who flits across the lighted hall,

loves, laughs, sorrows, sings and dies.

We come from darkness and to darkness we return.’

Augustine of Hippo ruled four things vex the mind:

sorrow, joy, desire and fear: a life denying them,

humourless, cloistered, penitential.

From darkness, to darkness, via silence.

Shoulder to shoulder in the shield wall, grim and resolute,

staring into a stranger’s hatred. Thrust of the spear shaft,

board arm numbed by the blows, brain numbed by the noise.

Then to walk, alive, amongst the dead.

To reaffirm this is not a ghost returning. To touch the rough door lintel.

Enter to their wary welcome, experience for once the beauty

of small, dull, ordinary things: old men’s complaints,

your children’s noise, the case of someone’s stolen chickens.

To be still and quiet as she washes blood, cleans wounds.

Eyes search for recognition. Is the one who left the one who has returned?

To see, dawn-lit, the colour of her skin. To wake beside her warmth,

remembering those who lie, eyes open, on the cold grass.

I’m Peeping Tom, the voyeur’s patron saint,

the sordid little man who peers inside

your house, and lurks in kiddies’ playgrounds?

Get off the grass. Behind the shuttered windows

sound of hoof-fall, exploding in the morning.

God-fearing folk all longing for a peek

who mistook fear of punishment for virtue

and dreamed her in their bedrooms for a week.

And me? The patron saint of curiosity,

Tom cat, but blinded, never killed.

I saw Beauty, radiant, riding naked

through the grubby streets at dawn.

From The Modern City

I came from Ireland, Scotland, Uganda, Jamaica,

from the crumbling ends of an empire,

from enclosed fields, from feudal landscapes,

to the walls and the streets and the factories.

Like an overstressed arch, linking there and here,

we oscillate between remembering and forgetting.

The smell of our cooking, the cut of our clothes.

The way our mouths negotiate the absurdities of English.

We bring our stories of the place we started from:

‘Home’ forever in past tense, to this place,

now, where the meaningless streets and parks,

wait to be made familiar in our children’s stories.

West Midlands Danny Boy.

Oh, Danny boy, the bloody pipes are frozen,

The toilet’s blocked, the rent man’s on his way.

Thank God you’ve got that job down in the factory

So what it’s shite, my Danny boy, it pays.

On Friday nights, we’ll drink to the auld cun-ter-ee

It’s mountains, valleys, rivers, feckin green.

We call it home, forget the grinding poverty

and sing about a place we’ve never seen.

But I’ll return, when winter rains are falling

I’ll find your house, I’ll walk along your strand,

I’ll know this place, its stories were my fairytales

and Danny boy, I think I understand.

You leave one place to seek it in another.

You can’t arrive, you’re stranded in between.

You remake home from songs and fading memories;

somewhere you left: somewhere you’ll never be.

No one told the women in my family

they were the weaker sex.

My grandmothers, worn by the century,

were beautiful, resilient and humane.

My English gran survived

both husband and the Blitz

and treated those disasters

much the same.

One daughter asked:

‘If Hitler comes, what shall we do?’

‘Leave him to me,’ she said,

‘I’ll sort the blighter out.’

A mythic landscape talked about in whispers.

The convent girls who giggled on the bus.

Lust, like a slide rule, something you’d encounter

and have explained to you in high school.

Like singing in a foreign language. The obscene

jokes and gestures that you never understood. Words

scrawled on toilet walls. That nameless place

where neck and shoulder meet, the way

a sudden movement turned the world to water.

With Lady Godiva’s statue in the rain,

patiently teaching anatomy to boys

before nudity was common on TV.

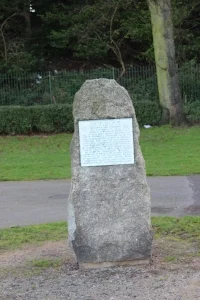

The stone in Gosford Green, commemorating something that didn't happen.

Lady Godiva and Me finishes with Talking nothing to the Stone, the stone is the memorial in Gosford Green. What follows are extracts.

Talking Nothing to the Stone

Nothing, like something, happens anywhere.

-Phillip Larkin I Remember I Remember

The year 1398 saw one of the greatest anti-climaxes in national history taking place, or rather, not taking place on Coventry’s Gosford Green

-Coventry Telegraph.

Yet like Lir’s children banished to the waters

Our hearts still listen for the landward bells.

-John Hewitt: An Irishman in Coventry.

This simple, ugly plaque records that sometime in the fourteenth century,

the date depends upon which source you use, Bolingbroke and Mowbray

didn’t fight a duel. My favourite stone, in all that’s left of Gosford Green,

beside new plastic swings, designed so no child breaks a bone.

Richard, a spineless king, by most accounts, decreed

the fight should stop before it had begun and both men would be exiled.

If they came back he’d have their guts for garters, according to my dad.

Unable to defend themselves, they left to pace their days out in a foreign land,

as I did, twenty years ago. But like Lir’s children, banished to the waters,

hearts listen for the landward bells. And so I have returned,

to stand here in the winter light and photograph this stone.

.....

If there was magic in the city walls

far from the factories and football

you’d find it there. A spiral stair

and high above the other browsers

an alcove where they kept the poetry.

Thank god for city libraries.

From Service and a dream

of Yukon gold, to Beowulf and Malory

and that was coming home and there he stayed.

The wandering scholar learnt his trade,

dreaming of study, and of bedding young librarians.

Ah, Gwenhaver.

The pubs had shut, the streets were whispering,

the traffic lights still sent instructions no one saw.

We sat on the old-fashioned swings,

the ones you could fall off and hurt yourself.

There was a party, see, she’d gone cos she was bored

and she was drunk. I was away. She met a boy,

you know. It started as a joke. Then there were stairs, a bedroom.

She couldn’t find the light. An adult’s double bed,

so vast the sheets got in their way.

The creaking swings,

an empty double-decker fades towards the morning.

............

Exactly what took place? Well, Bolingbroke and Mowbray

were armed and ready, there’s a clichéd version says that Henry had set off.

His lance was levelled, shield gripped tight: he’s thundering down the lists.

The heralds cry: Hold, Hold, before the spears could splinter.

They dismount, return to cushioned chairs, and wait

for hours until the dodgy king makes up his mind.

What I see now, perhaps, he couldn’t.

It’s not the nothing Larkin moaned about.

I do remember being interstitial.

Not quite rejected: I grew up over there;

a house with roses rambling up the front

in a road named after Henry Bolingbroke.

Even learnt to speak West Midlands though

dad’s brogue, which reappears when I begin to sing,

denies me local authenticity.

If he’d gone home after the war,

I would have sung the old songs in a decent accent,

but my father, and his father, and his father’s father

and my mother, and her mother, and her mother’s mother,

not one lies buried in the town where they were born.

Movement, away from or towards,

becomes a natural habitat. Trains, planes, boats

libraries or cars: to circumnavigate the globe

to seek new ways of seeing and to see.

It’s only exile if you have no curiosity.

(John of Gaunt, if memory serves.)

..........

So Richard Mowbray went abroad and died,

heart-broken many say. Ambition should be made of sterner stuff!

(Another local writer has his two bob’s worth.)

Unlike our Henry Bolingbroke, hard man for hard and ugly times,

who did return, within the year, to claim the kingdom as his own.

Richard, captive, paraded through the town where he had sat as judge.

So Fortune and her wheel, in medieval thought, a blind bitch with no loyalties.

So Henry sitting in his cushioned chair, waiting to know if he would die that day.

I wonder if he too came here, to stand alone in failing light,

and contemplate what might have been.

Or did he spit on Coventry as he rode past?

It’s far too dark to take a photograph.

What didn’t happen seems so overrated:

the girl, the job, the move he never made.

Too busy waiting for the first bus out of here

to notice all the ones queued up to take him home.

I know this place, but wouldn’t claim it mine.

Mine is the space between the rising and the falling foot.