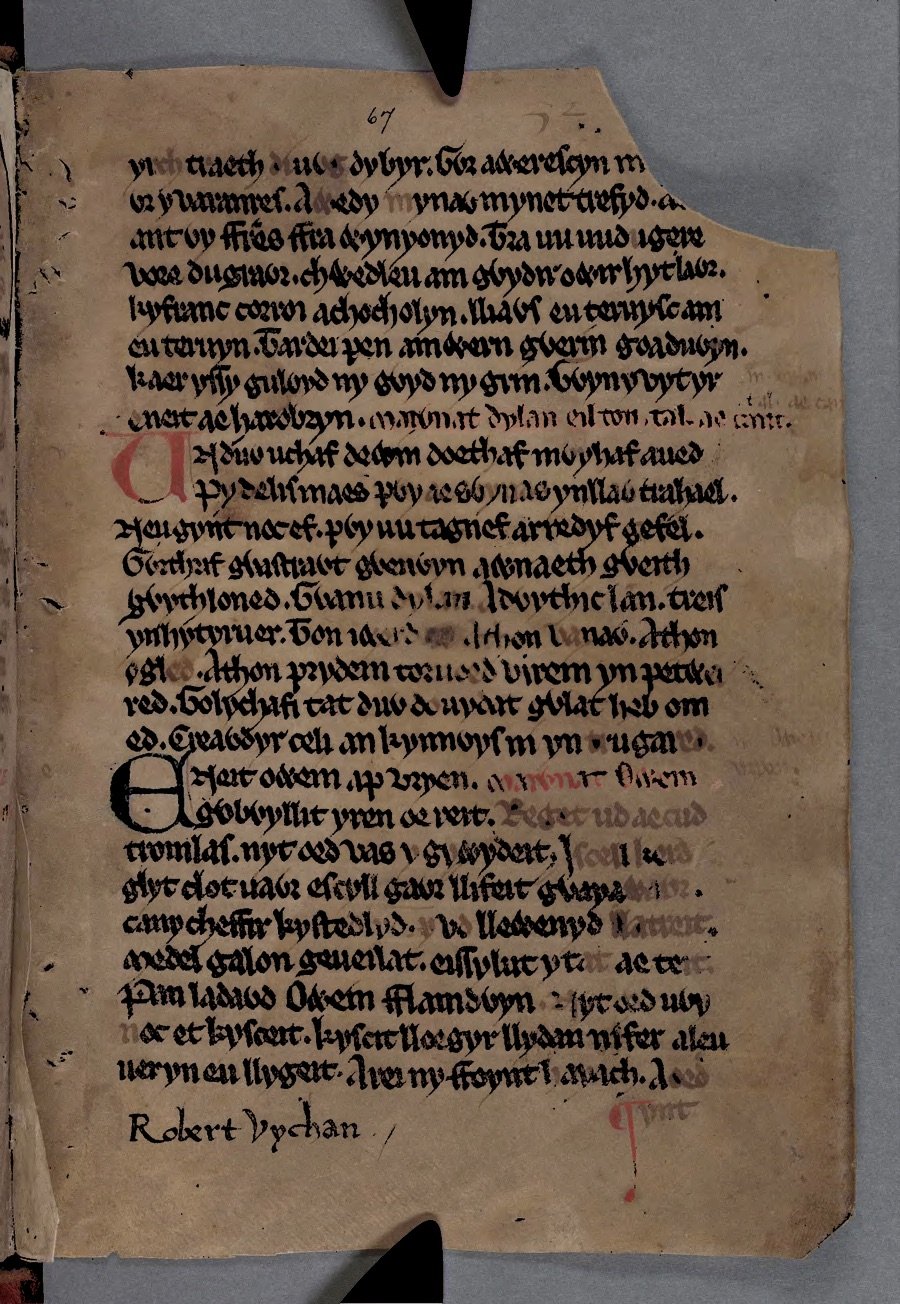

A page from the Book of Taliesin showing the start of Marwnat Owain at the Large black capital.

Taliesin (6th Century)

There are at least two Taliesin’s. There was an Historical bard who composed poetry in the courts of ‘Welsh Princes’ in the Sixth Century, a contemporary of Aneirin. There was also a character from a folk tale, who gained knowledge and inspiration from a cauldron he was stirring, and after many transformations was born again as a miraculous child who could speak as soon as he was born and went on to be a magician and prophet as well as a poet.

The Book of Taliesin is one of those precious medieval manuscripts which are worth their weight in Guttenberg bibles. It dates from the 14th century, and the two figures have obviously merged. Brilliant scholars have spent their careers trying to untangle the poems, trying to date which may belong to the Historical Bard and which have been attributed to him. Most seem to think this one might be ‘authentic’.

It’s a marvellous controlled howl of a poem that belongs to a very different world. “King’ and ‘Prince’ dignify men who spent their lives raiding and being raided by their neighbours. Enthusiastic cattle thieves. It’s also a world where poetry served a very public function and the poet was an honoured member of the court.

Taliesin laments the dead Owein by celebrating highlights from his ruthless destruction of his enemies. The highest praise possible is to state that he was a generous, ferocious killer. The line ‘Medel galon geueilat’ could be translated almost literally as ‘A reaper of foes, a predator’.

This translation is taken from The Book of Taliesin, Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain, translated by Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams. Penguin Classics 2020.

My pronunciation is not up to inflicting the original on an audience, but if you can, find a Welsh speaker reading the original.