Robert Browning (1812-1889)

There’s a story. A bemused reader asked Browning what this poem meant. ‘Well,’ said the poet, ‘when I wrote it only God and Robert Browning knew. Now only God knows.’

Sadly this conversation didn’t take place, and the comment was most likely made by a character called Robert Browning in a play. But it’s worth keeping in mind. There’s nothing wrong with worrying about ‘what it means’ but a better question with this poem is what does it do to you while you hear it or read it. What do the images suggest, the words evoke? Go along for the ride and experience the story before you start worrying about what it means.

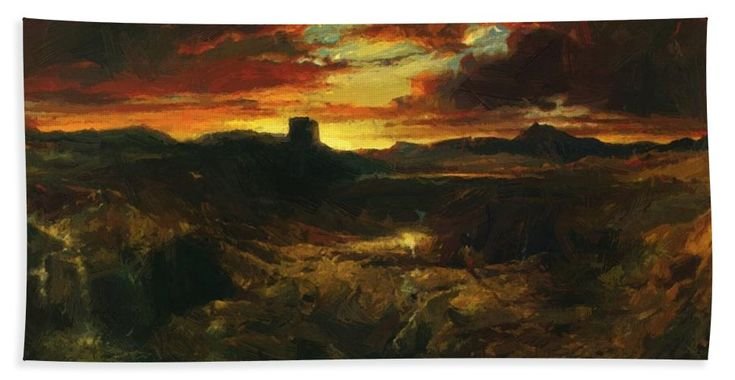

The irrational came into English Literature at the end of the 18th Century with the first wave of Gothic literature. It was given substance in English poetry by Coleridge, and you can trace it through the 19th century. Browning’s Childe Roland and Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market are two of the finest examples.

Stephen’s King ‘Dark Tower’ series ostensibly begins as a riff on this poem. But if you want a version, then Louise MacNeice’s play ‘The Dark Tower’ does a better job of capturing the spirit of the original.