Men of the Royal Irish Rifles in the opening hours of the battle of the Somme 1916

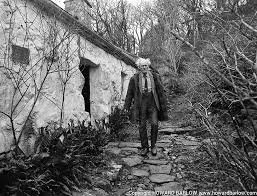

Wilfrid Owen (1893-1918)

The last of a short run of poems in which poets use familiar names and stories in their poems.

In the Book of Genesis ,Abraham is tempted by God, who tells him to sacrifice his only son. Obediently Abraham takes Isaac, and is prepared to kill him, but God interrupts and offers him an animal to sacrifice instead.

One wonders about the conversation between father and son on the way home.

Owen’s poem revises the well-known story. The old man refuses to sacrifice the Ram of Pride God offers him, and goes on with the slaughter. As statement the poem’s effective, as a poem it’s heavy handed.

The archaic diction and syntax evokes the memory of the prose of the King James Bible; but the ‘belts and straps’ and ‘parapets and trenches’ seem an unnecessary attempt to force the link between Biblical sacrifice and the trenches and parapets of the first world war, manned by young men wearing belts and straps. I’ve always felt that he didn’t trust his readers to make that link

At the risk of being heretical, Leonard Cohen’s lyric to the song ‘The story of Isaac’ makes the same point more powerfully, and more effectively.